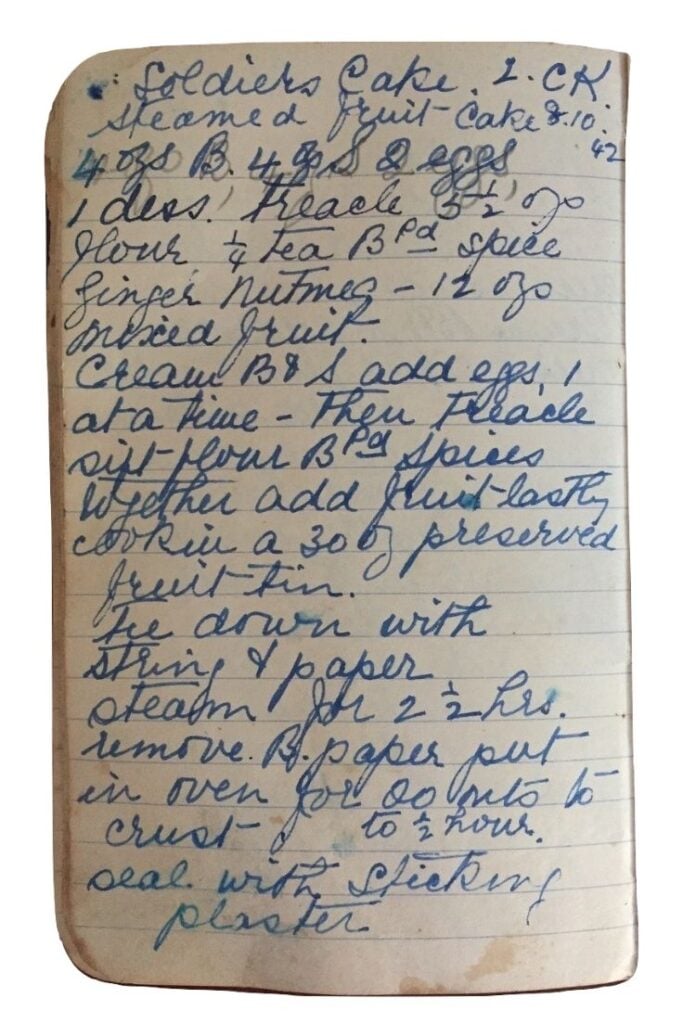

Nana Ling recorded this recipe for Soldiers Cake on 8 October 1942.

At that time, the end of the Second World War was still a long 2 years and 10 months away, though the Australian Army was just days away from playing an important role in the Allied victory at El Alamein in Egypt.

Soldiers Cake is a fruit cake and this recipe contains instructions for sealing the cake in a tin. That, and the name, suggests it was intended to be packaged up and sent to those serving overseas.

During the Second World War, 575,799 Australians served overseas, 39,429 were killed and 66,563 were wounded. The figures are sobering. And this cake recipe is a small reminder of the heartache, hope and helplessness people must have felt at the time.

To better understand the history behind this recipe, I spoke with a curator from the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Soldiers Cake

An interview with Dianne Rutherford, Curator in Military Heraldry & Technology at the Australian War Memorial

It seems this soldiers cake recipe was something that was intended to be cooked and sent to people serving overseas. Can you shed any light on this recipe?

A lot of people baked items during the First and Second World Wars to be sent overseas. Fruit cakes last particularly well. If well-made and well-packed they can last for quite some time. This is important because in both World Wars, you could have weeks to months from when you posted it until when it was received.

They're also pretty sturdy, they won't crumble like a biscuit – though people did send biscuits too. Fruit cakes also have some nutrition in them too.

I noticed with Nana Ling's recipe there's no alcohol, which is quite interesting. A lot of these recipes will have brandy or rum, just a little bit, but this one doesn’t.

Nana Ling often included the source of the recipe, but didn't for this particular recipe. Do you know where she may have found it?

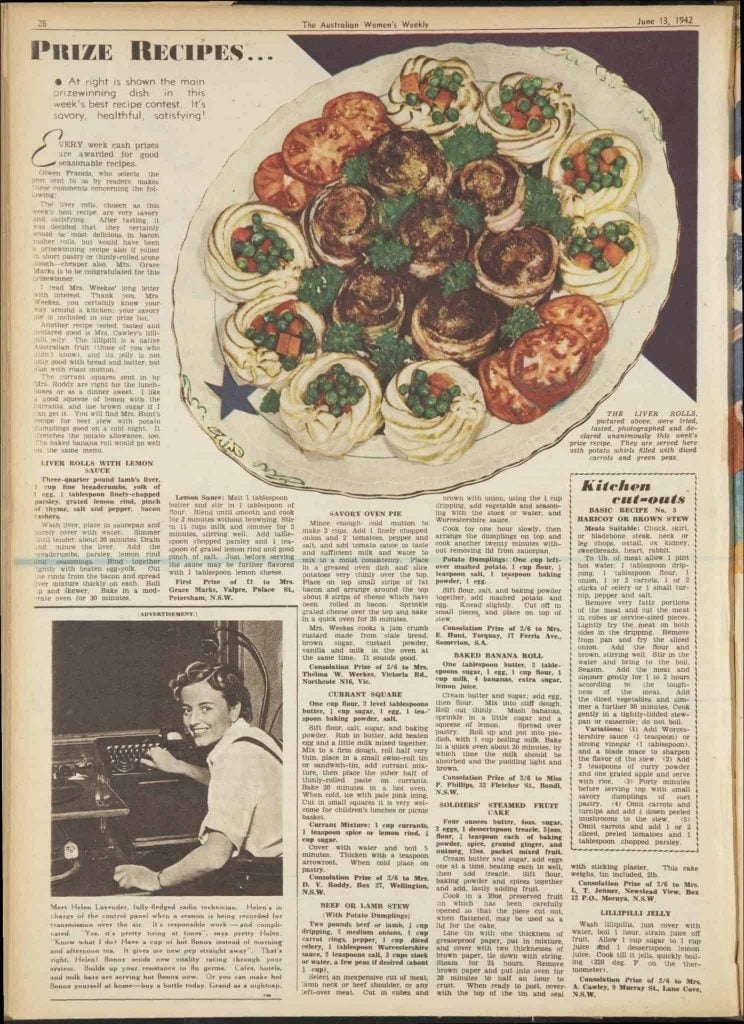

I actually did find your great grandmother’s recipe. The earliest reference I can find to it is it being published in the Australian Women’s Weekly (AWW) on 13 June 1942. It gets republished on 1 August 1942 and, subsequently, other women send it into newspapers. So, in 1943 it’s in a Queensland newspaper and a Melbourne newspaper and in 1945 it’s in a Tasmanian newspaper.

When it’s republished in the AWW in August, the magazine article explains why:

“Time and time again come requests for good but not expensive fruit cake. This is the reason why Mrs Jenner’s steamed fruit cake has been chosen for the main prize. It is good; inexpensive to make, too. Moreover, she has solved the packing problem in the recipe. This should be of particular interest to readers who desire to send cakes along to the lads in the services.”

When these cakes were sent overseas, were they sent to a particular person or a general address? How did it work?

A bit of both. Family members would send items to loved ones, but there were also a number of comfort organisations. So, as well as Red Cross, there were a bunch of smaller ones as well. They would often organise to send things to specific units or to lists of people.

Different organisations would ask for people to bake for them. It was particularly popular. Biscuits were sent as well but there was an issue with breakage.

What happened to this tradition? Do people still send cakes or other treats overseas today?

It still actually happens.

During the Vietnam War, a tin full of ANZAC Biscuits was sent to an Australian soldier, Terry Hendle. He was mortally wounded the evening after he received the biscuits from his mum. The unopened tin went back to her and she kept it for the rest of her life. Then Terry's sister kept it for a number of years before donating it to the Australian War Memorial. I wrote a blog post about it.

Once you start getting into the Vietnam era, and even to some degree World War II, you are getting a lot more manufactured things. But people are still making things for their loved ones, and they’re often very popular. Terry used to share his ANZAC Biscuits with the guys he was serving with.

Even today, it’s not as common, but one of my colleagues went to Iraq a year or two ago and the area she went to, a lady had got the name of one of them and she’d bake chocolate chip cookies and send them to Iraq. They were home baked and they were very popular. It’s not common but it does happen.

Sometimes Defence will do a bit of a drive to send parcels to the troops at Christmas or at different times, too. When we were quite heavily in Iraq and Afghanistan, Defence had an address you could send things to and they would allocate it out. They usually have specific recommendations about what you can include and the box size you should use. You pay for the box and then they pay for postage if you conform to the box size.

It’s a bit different now for people serving overseas because they can get some things more easily than you could back in the old days. But they still do appreciate a few treats – knowing someone’s thinking of them, someone’s actually gone to the effort of actually making something and sending it.

Is there anything else you found particularly interesting about this recipe?

The fact that it is steamed is interesting. I’m not sure whether it’s a preservative measure or just something to make it taste nicer.

The reference to sticking plaster is a reference to bandages to help seal it up and make sure no air gets in. Because it’s not made in a regular tin, it wouldn’t have a lid and would need to be sealed up.

Thank you Dianne for generously sharing your knowledge.

Cooking Soldiers Cake today

Can you still cook fruit cake in a preserved fruit tin?

This recipe solves the problem of packaging up the cake to send overseas, at least in part, by suggesting the cake be cooked in a preserved fruit tin.

Before cooking the recipe, I contacted Australian fruit processor SPC to find out whether it's still safe to cook in a preserved fruit tin.

The answer? No, it's no longer recommended since a higher gauge steel was used back in the 1940s.

So, to cook this recipe I used a small, deep and round 15 cm cake tin.

How do I steam a fruit cake?

Steaming a fruit cake is not too difficult, even if you don't have a steamer.

Simply place a small ceramic or pyrex dish at the bottom of a large boiler.

Fill with water until the level reaches the top of the small dish.

Place cake, covered with paper that is secured with string, on top of the dish, place lid on boiler and then bring water to the boil. Check from time to time as you may need to top up the water level (I did this twice during the 2 ½ hours of steaming).

Sending fruit cake to those currently serving overseas

Following this interview, I contacted the Department of Defence about how members of the public can send care packages to Australians serving overseas (there's 2,300 serving overseas on Anzac Day 2018). You can send care packages and messages of support following this procedure.

This page explains the process.

Nana Ling's Soldiers Cake recipe

Keep scrolling for the tested and tweaked version below.

Soldiers Cake

Ingredients

- 115 grams butter

- 115 grams sugar

- 2 eggs

- 1 dessert spoon treacle

- 155 grams flour

- ¼ teaspoon baking powder

- ¼ teaspoon ginger

- ¼ teaspoon nutmeg

- 340 grams mixed fruit

Instructions

- Cream butter and sugar.

- Add eggs, one at a time.

- Add treacle and mix well.

- Sift flour, baking powder and spices into mixture and stir to combine.

- Add fruit and mix well.

- Put mixture into a small, deep cake tin which has been lined well with baking paper. (A 6 inch round tin works nicely with 3 layers of greased baking paper).

- Cover cake tin with a piece of baking paper and tie to secure.

- Steam for 2 to 2 ½ hours.

- Remove paper cover and put into a slow oven for 20-30 minutes to crust.

- Remove from oven, cover with aluminium foil and wrap in a clean tea towel to cool.

Leave a Reply